The Science of Storytelling: A Powerful Tool for BCBAs

Storytelling and Behavior Analysis: A Shared Foundation

Behavior analysis and storytelling might seem like separate disciplines, but they share a fundamental connection—both shape behavior through carefully arranged contingencies. Our field’s history includes powerful narratives, none more influential than Catherine Maurice’s Let Me Hear Your Voice, a firsthand account that introduced countless families to behavior analysis. Storytelling has always been a vehicle for disseminating science, yet we often underestimate its strategic role in shaping public perception and policy. I’ve spent years leveraging narrative in behavior analysis, whether through filmmaking, multimedia dissemination, or large-scale data analysis. When capturing discussions with thought leaders like Steven C. Hayes—one of the most highly cited researchers across all sciences—I’ve seen firsthand how behavior analysis is still defining its larger story. Skinner’s last words highlight this ongoing evolution: “A better understanding of variation and selection will mean a more successful profession, but whether behavior analysis will be called psychology is a matter for the future to decide.” Just as variation and selection drive scientific progress, storytelling helps shape how that progress is understood and adopted.

This intersection becomes even clearer when considering stimulus control, the organizing principle that connects behavior to the environment. Storytelling itself is a form of stimulus control—it alters the way people respond, understand, and engage with behavior science. The challenge, as Ed Morris (1985) warned, is ensuring our field arranges the contingencies necessary for its own survival. We face resistance from within, with some organizations failing to see the value of interdisciplinary collaboration. However, by integrating storytelling into dissemination strategies, we can expand behavior analysis beyond traditional boundaries, reaching new audiences and reinforcing its scientific credibility. I’ve had the opportunity to apply these principles with leading figures in the field, including Greg Hanley and the Practical Functional Assessment and Skill-Based Treatment model, Study Notes ABA's test prep service, and Patrick C. Friman at Boys Town. Each of these initiatives required not just expertise in behavior analysis, but also a deep understanding of how to frame and communicate complex scientific ideas in ways that resonate with practitioners, parents, and the broader community. If we approach our work with the same precision we bring to research—embedding clear, pragmatic goals into our storytelling—we can ensure that behavior analysis remains not just relevant, but indispensable to solving real-world problems.

Science Communication (SciCom)

Ronny Detrich captured a central paradox of behavior analysis when he wrote, “It is somewhat ironic that what is arguably a science of influence (behavior analysis) has not been more effective at influencing the adoption rate of a science of influence.” (Detrich, 2018). When I met him at a conference, he had just finished working on this article, and our conversation was pivotal in shaping my own exploration of this issue. His work reinforced something that many in the field had already suspected: our specialized language might be limiting the impact of behavior analysis. Empirical research supports this idea, showing that the technical jargon we use may act as a barrier to broader adoption (Becirevic, Critchfield, & Reed, 2016; Critchfield et al., 2017; Jarmolowicz et al., 2008). If we want behavior analysis to be more widely understood and applied, we need to rethink how we communicate—not just by simplifying language but by strategically refining our entire approach to dissemination.

Detrich pointed me toward Randy Olson’s Houston, We Have a Narrative, a book that directly addresses the communication gaps scientists face. But I didn’t just read the book—I had to see Olson’s methods in action. At the time, he was working with scientists on a project in Las Vegas, helping them use storytelling techniques to structure their messages for broader audiences. He generously welcomed me into his workshop, giving me the opportunity to experience his approach firsthand. Olson’s model provides a framework that behavior analysts can use to make their work more compelling, memorable, and actionable. If our goal is to truly influence behavior at scale, we need to embrace the power of narrative. So, let’s break down Olson’s approach and explore how it can help us bridge the gap between behavior science and public understanding.

Randy Olson, a marine biologist-turned-filmmaker, opens Houston, We Have a Narrative with a striking observation: storytelling can drive scientific engagement. He points to Jurassic Park (1993) as an example, a film that not only dominated the box office but also led to an uptick in museum attendance and applications to archaeology programs. This cultural shift sparked Olson’s interest in how narrative influences public perception of science. When he later suggested to fellow scientists that they frame their presentations as stories, he faced resistance—science, after all, is deeply personal, and shifting one’s narrative can feel like a challenge to authority. Scientists are trained to present facts as they are, without embellishment, but Olson realized that ignoring narrative structure meant limiting their reach. He saw a disconnect: the scientific community prides itself on precision, yet its communication often lacks the clarity and engagement needed to influence a broader audience.

To illustrate his point, Olson references the iconic “Houston, we have a problem” line from Apollo 13. The actual words spoken during the 1970 crisis were, “Houston, we’ve had a problem here,” but the film adaptation altered it for brevity and impact. This, Olson argues, is what scientists must do—retain accuracy while adapting to the narrative world. However, this idea unsettles many in science. As Olson notes, “Rearranging things comes with risk—at the mildest, just getting it wrong, at worst, deceiving people.” Scientists worry that shaping their message could distort their findings, but the reality is that they already do this within the constraints of academic publishing. Nobel laureate Peter Medawar criticized the structure of scientific papers, arguing that they present an artificially clean version of the research process. Similarly, behavior analyst J.R. Kantor questioned whether the field truly adheres to an inductive approach. Olson challenges scientists to embrace a three-step process: see it, shape it, say it. If we want to influence behavior and policy, we must actively refine our communication without sacrificing scientific integrity. In fact, scientists already shape their work—structuring and refining their findings is an inherent part of the writing and publication process in empirical journals.

Applied Behavior Analysis Is Indebted to Storytelling

Catherine Maurice’s Let Me Hear Your Voice is one of the most influential narratives in the history of behavior analysis, particularly in the adoption of Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention (EIBI) for autism spectrum disorders. Before diving into why, let’s revisit Ronny Detrich’s perspective on dissemination. He reminds us that dissemination is not simply about publication—it’s about successful adoption. “Behavior analysis is rooted in pragmatism (Hayes, 1993) and its truth criterion is successful working with respect to a particular goal. From the perspective of pragmatism, a definition of dissemination is that it has been achieved only when a practice has been adopted (successful working).” (Detrich, 2018). Many assume that dissemination occurs as soon as an article is published, but a functional approach—one that focuses on actual impact—reveals that dissemination only truly happens when behavior change occurs. This insight is critical when considering how Let Me Hear Your Voice played a role in the widespread adoption of behavior analysis in autism intervention. Maurice did not publish a research paper; she wrote a compelling, personal account of how behavioral therapy helped her children recover from autism. And that, more than any statistical table, moved people to action.

Maurice’s book tells the story of her struggle to find effective treatment for her two autistic children. Traditional professionals offered little hope, but through persistence, she discovered behavior therapy and hired dedicated therapists. Over time, she witnessed remarkable progress in her children—first Anne Marie, then Michel. The book not only describes the challenges of autism but also highlights the effectiveness of behavior therapy in a way that parents and the broader public could understand. This is precisely why storytelling matters in dissemination. As Detrich points out, “She most likely would not be remembered as one of the great disseminators of applied behavior analysis had she penned a summary of evidence on its effectiveness. Her story had the capacity to bring tears in a way that no statistical table ever could.” (Detrich, 2018). The research was necessary to validate EIBI, but it was not sufficient to drive its adoption. Maurice’s book became a catalyst for change because it spoke to people’s lived experiences and provided a narrative of hope and success.

The impact of Let Me Hear Your Voice on the field of behavior analysis cannot be overstated. As Detrich notes, “The wide-scale adoption of early intervention for children with autism is the most successful dissemination effort in behavior analysis. Let Me Hear Your Voice was a major impetus for this.” (Detrich, 2018). It was not just the science that convinced parents and policymakers to advocate for EIBI—it was the story. This aligns with Rogers’ (2003) framework on the factors influencing the adoption of innovations. According to Rogers, four key factors determine whether an innovation will be widely adopted:

- it must solve an important problem for the client

- it must have a relative advantage over current practices

- the person promoting it must be credible, and

- it must be compatible with the values, experiences, and needs of the audience."

Let Me Hear Your Voice succeeded in all four areas—it addressed a dire need for effective autism intervention, demonstrated a clear advantage over existing options, was written by a credible source (a parent with firsthand experience), and aligned with the hopes and desires of other parents searching for answers.

This brings us back to the broader challenge of disseminating behavior analysis today. If storytelling played a crucial role in the widespread adoption of EIBI, what lessons can we apply to other domains of behavior analysis? As behavior analysts, we often focus on evidence, data, and precision—but if we want our science to influence society at large, we must also consider the emotional and narrative components of communication. Maurice’s book worked because it framed behavior analysis in a way that was accessible, relatable, and actionable. Today, as we seek to expand the impact of behavioral technologies beyond autism treatment, we must recognize that dissemination is not just about what we say—it’s about how we say it. The challenge ahead is clear: how can we craft narratives that capture the power of behavior analysis and make it resonate with those who need it most?

Was A Book All That It Took?

A single book was not solely responsible for the widespread adoption of early behavioral interventions—it was just one piece of a much larger system. From a systems analysis perspective, multiple variables contributed to the expansion of applied behavior analysis (ABA) in autism treatment. Medical models rely on empirical support, professional organizations, and certification systems, all of which were present in ABA’s development. At the time, ABA had the only empirically supported evidence-based practice for autism, the BACB was establishing certification standards, and professional organizations provided a home for continued research and development. Additionally, funding—both public and private—helped solidify ABA’s place in treatment models. The alignment of these factors created what could be described as the perfect storm for dissemination. However, one major flaw in behavior analysis remains: we often engage in inreach, speaking to those already within our field, rather than outreach, where we actively engage new audiences. As Morris (1985) warned, “If a scientific community does not arrange for contingencies that assure its survival, then so much the worse for that community, and for the rest of the culture at large.” If behavior analysis is to thrive, it must adopt broader dissemination strategies beyond academic journals and conferences.

Detrich (2018) emphasizes that our current dissemination efforts are ineffective for reaching non-behavior analytic audiences. “The most common dissemination efforts by behavior analysts are publications in scholarly journals and presentations at professional conferences. These efforts reach a very small subset of the potential audience.” The reality is that parents, educators, physicians, policymakers, and other stakeholders in behavior change do not typically engage with academic publications or conference presentations. If we want to influence adoption rates, we must use media and communication strategies that actually reach them. Two key points emerge from this discussion. First, dissemination must be functional and pragmatic, targeting specific audiences with tailored messaging. “It is important to recognize that not all audiences are the same and will not be affected by the same story.” Second, scientists—including behavior analysts—are not necessarily the best storytellers. Maurice, for example, was arguably more effective at promoting behavior analysis for autism than Ivar Lovaas, not because of her scientific expertise but because of her ability to craft a compelling and relatable narrative. Traditional scientific communication, with its rigid structure and technical language, may be a barrier rather than a bridge to public understanding. If behavior analysis wants to expand its influence, it must move beyond academic discourse and embrace storytelling as a powerful tool for dissemination.

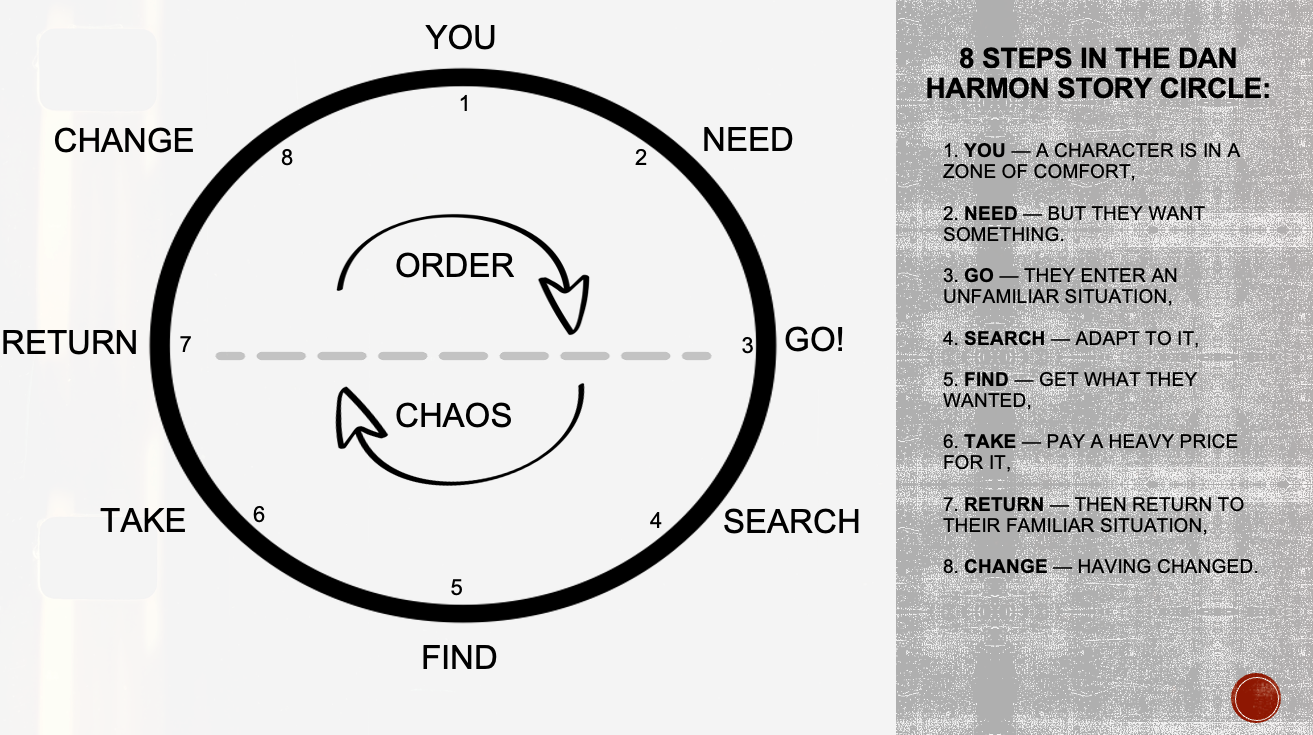

Dan Harmon’s Story Circle provides a powerful alternative to traditional storytelling structures like the Hero’s Journey, and it’s a tool that behavior analysts can leverage to improve communication and dissemination. Instead of a linear journey, Harmon’s model follows a cyclical pattern that mirrors the natural progression of change—something deeply relevant to behavior analysis. The circle consists of eight stages: (1) a character in a zone of comfort, (2) they desire something, (3) they enter an unfamiliar situation, (4) they adapt to it, (5) they get what they wanted, (6) but they pay a price, (7) they return to where they started, (8) but they have changed. This structure aligns closely with behavior change itself—whether in an individual’s treatment journey or in the broader adoption of behavior analysis as a discipline. The beauty of the Story Circle is its flexibility; it can be applied to any format—whether visual (videos and ads), auditory (podcasts), or written (websites, books, and research papers).

I have used this process to craft highly effective and powerful stories about behavior analytic services, ensuring that their impact is communicated to the right audiences in a way that resonates and drives action. A recent example of this work is my collaboration with Kent Johnson and Morningside Academy, an institution known for its precision teaching methods and transformative educational outcomes. By structuring the narrative around the real-world successes of students, the science behind Morningside’s approach, and the urgency of effective educational interventions, I was able to help shape a compelling story that engages both practitioners and the general public. Just as Catherine Maurice’s Let Me Hear Your Voice played a pivotal role in the widespread adoption of early intervention, well-crafted storytelling can accelerate the adoption of effective behavior analytic technologies across domains. Whether it’s in education, clinical applications, or organizational behavior management, the strategic use of narrative ensures that behavior analysis is not just heard but truly understood and valued.

Many organizations already use structured narrative frameworks to improve outreach. For example, Harmon’s Story Circle has been implemented in public communication strategies by agencies like the National Park Service and even the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The reason is simple: storytelling influences behavior. In behavior analysis, we recognize that shaping is essential for skill acquisition—narrative training follows the same principle. Whether structuring journal articles (IMRAD: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) or creating persuasive media campaigns, mastering storytelling is a skill that takes refinement. By integrating the ABT model as a starting point and expanding into the Story Circle, behavior analysts can better frame their findings in ways that engage and persuade. Just as we measure progress in behavior change, we should also set goals for the effectiveness of our storytelling—because, ultimately, the success of our science depends on how well we communicate it.

As Ronnie Detrich so powerfully stated, our task as behavior analysts is twofold: to contribute to the scientific understanding of narrative while also using it as a tool to disseminate our findings more effectively. If we want behavior analysis to thrive, we must push beyond inreach and into outreach—just as our field’s pioneers did. Whether you’re looking to improve your dissemination strategies, refine your marketing, or enhance how you communicate your work, I offer consultation services to help you implement these principles effectively. If you’re interested in working together, feel free to reach out via email. Additionally, if you want a deeper dive into these concepts and a structured path to mastering them, I highly encourage you to sign up for my course on Social Media and Applied Behavior Analysis, where I break down these methods and more in detail. Let’s build a better science, a stronger field, and more impactful stories—together.

References

- Becirevic, A., Critchfield, T. S., & Reed, D. D. (2016). On the social acceptability of behavior-analytic terms: Crowdsourced comparisons of lay and technical language. The Behavior Analyst, 39(2), 305–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-016-0067-4

- Critchfield, T. S., Doepke, K. J., Epting, L. K., Becirevic, A., Reed, D. D., Fienup, D. M., ... Ecott, C. L. (2017). Normative emotional responses to behavior analysis jargon or how not to use words to win friends and influence people. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 10(2), 97–106.

- Detrich, R. (2018) Rethinking Dissemination: Storytelling as a Part of the Repertoire. Perspectives on Behavior Science (2018) 41: 541.

- Jarmolowicz DP, Kahng S, Ingvarsson ET, Goysovich R, Heggemeyer R, Gregory MK. Effects of conversational versus technical language on treatment preference and integrity. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2008;46(3):190–199. doi: 10.1352/2008.46:190-199.

- Hayes, S. C. (1993). Analytic goals and the varieties of scientific contextualism. In S. C. Hayes, L. J. Hayes, H. W. Reese, & T. R. Sarbin (Eds.), Varieties of scientific contextualism (pp. 11–27). Context Press.

- Maurice, C. (1993). Let me hear your voice: A family's triumph over autism. New York: Knopf.

- Morris E. K. (1985). Public information, dissemination, and behavior analysis. The Behavior analyst, 8(1), 95-110.

- Olson, R. (2015) Houston we have a narrative: why science needs story. London: The University of Chicago Press

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press.

About the Author:

Ryan O’Donnell, MS, BCBA is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) with over 15 years of experience in the field. He has dedicated his career to helping individuals improve their lives through behavior analysis and are passionate about sharing their knowledge and expertise with others. He oversees The Behavior Academy and helps top ABA professionals create video-based content in the form of films, online courses, and in-person training events. He is committed to providing accurate, up-to-date information about the field of behavior analysis and the various career paths within it.