Beyond Baer, Wolf & Risley: The Nuanced History of ABA

If you ask most people where Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) began, they’ll point to Baer, Wolf, and Risley’s 1968 article—the one that defined the field’s seven core dimensions. But here’s the twist: ABA didn’t start there. The real story is more complex, more fascinating, and—like all good stories—it challenges what we think we know.

Storytelling isn’t just an art; it’s a science of behavior change. A well-told story functions like a structured sequence of verbal behavior, carefully shaping the listener’s understanding, beliefs, and actions. In behavior analysis, storytelling does more than entertain—it educates, persuades, and transforms. It helps us make sense of history, recognize the patterns that led to major breakthroughs, and understand why the field evolved the way it did.

So, what’s the real story of ABA’s origins? To get there, we need to go beyond Baer, Wolf, and Risley and look at the pioneering work that came before them—the research programs, the key figures, and the groundbreaking applications that truly set the stage for behavior analysis as we know it today. Buckle up, because this story is bigger than you think.

The Foundational Story: Baer, Wolf, and Risley (1968)

The field of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) is often referenced as beginning with Baer, Wolf, and Risley’s (1968) seminal article, Some Current Dimensions of Applied Behavior Analysis. This publication outlined the seven defining dimensions of the field—applied, behavioral, analytic, technological, conceptually systematic, effective, and generality—which continue to shape the practice of ABA today. Many training programs refer to this article as the origin point of applied behavior analysis, positioning it as the foundation of how interventions are developed and assessed. While its significance is undeniable, the history of applied behavior analysis extends beyond this publication. The roots of ABA can be traced further back to earlier experimental work and the shaping of operant principles long before 1968. Understanding the history of applied behavior analysis requires us to look beyond Baer, Wolf, and Risley (1968) and consider the contributions of other key figures and events that led to its development.

Sid Bijou

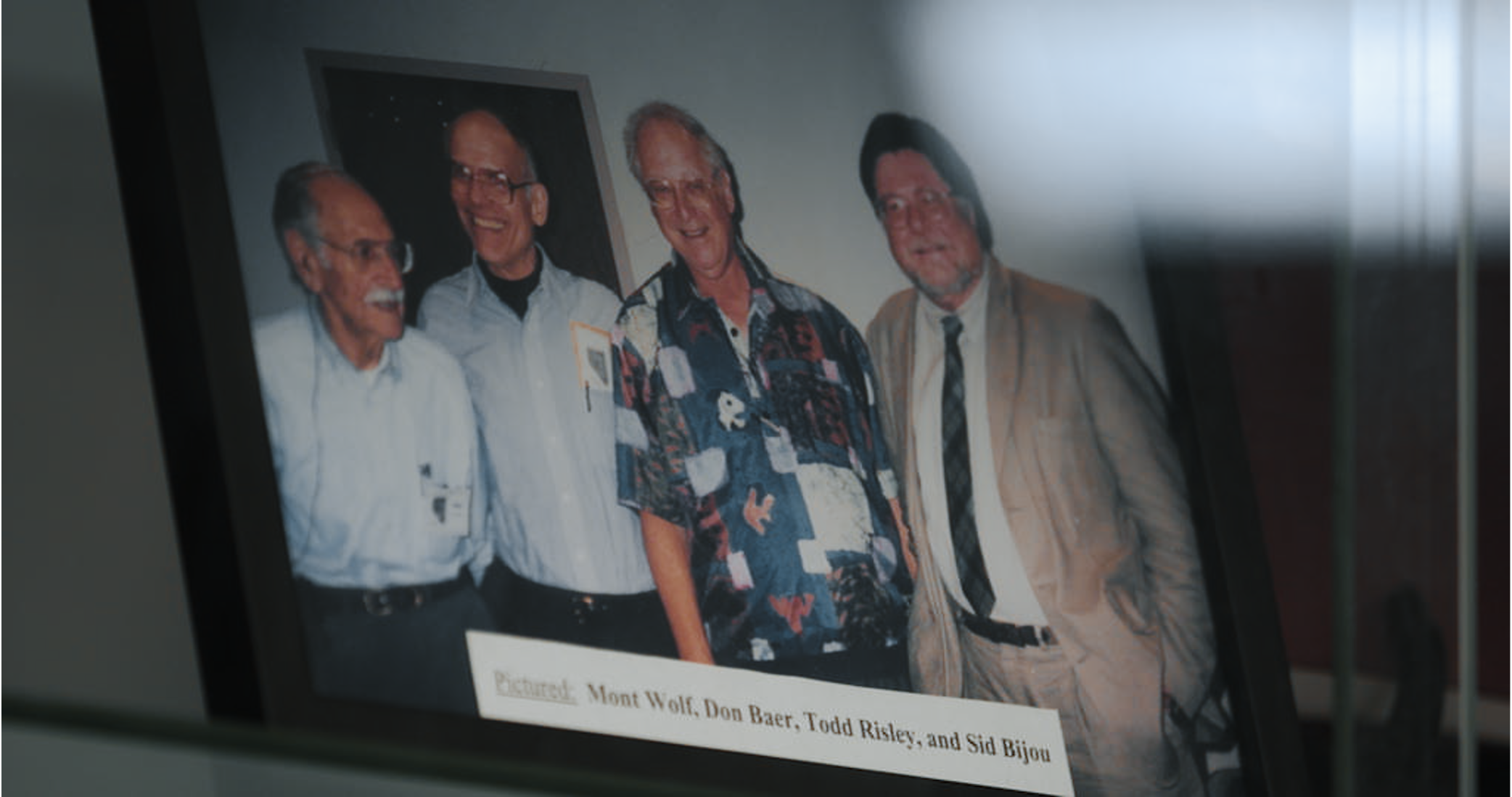

Sidney W. Bijou was a pivotal figure in the development of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), particularly through his work in early childhood behavior and learning. As a professor at the University of Washington, Bijou was instrumental in shifting behavior analysis from a primarily experimental science to an applied discipline, focusing on how operant principles could be used to improve children's learning and development. He mentored Donald Baer, Mont Wolf, and Todd Risley, who later became central to ABA’s formalization at the University of Kansas. Bijou’s influence extended beyond his mentorship—his research laid the foundation for behavior analytic approaches in education and child psychology, emphasizing systematic observation, reinforcement strategies, and individualized instruction. His work at the University of Washington’s Institute for Child Development directly shaped the methodologies that Baer, Wolf, and Risley would later refine and expand upon, solidifying ABA as a field dedicated to meaningful, socially significant change.

The Nuanced Publication Timeline of Applied Behavior Analysis

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) as a scientific discipline was founded through a series of key publications between 1959 and 1967, laying the groundwork for the field’s evolution. Morris, Altus, and Smith (2013) conducted a systematic study of these founding publications, categorizing them into three major research programs and other significant contributions. Their findings highlight the field’s complex origins, emphasizing that the identification of founding works depends on methodological choices and the evolutionary nature of ABA. The article argues that defining a singular “first” publication is difficult due to the various influences shaping ABA, from earlier behavioral research to the development of its core methodologies.

Among the most influential early works were the research programs of Ted Ayllon, Art Staats, and Mont Wolf. Ayllon’s studies on psychiatric patients demonstrated the application of operant conditioning principles to socially significant behaviors, sparking interest in behavior modification. Staats’s research focused on teaching reading and token reinforcement systems, which later influenced the development of behavior management strategies in educational settings. Meanwhile, Wolf’s work on treating severe problem behaviors in children, particularly his studies on “Dicky,” became a cornerstone in the behavioral treatment of autism and developmental disabilities. These programs exemplified ABA’s defining characteristics—applying operant principles to real-world problems while emphasizing measurable, observable behavior changes.

Beyond these major research programs, 24 other publications contributed to ABA’s foundation, covering diverse applications such as reducing bedtime tantrums, improving classroom behavior, and modifying psychiatric symptoms. The study highlights that many of these early works predate the establishment of the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis (JABA) in 1968, suggesting that the field was already forming before it had a formal identity. These studies established ABA’s emphasis on using systematic experimentation to produce meaningful behavior change, a principle that remains central to the field today.

Ultimately, Morris et al. conclude that determining the “true” founding of ABA is inherently unresolved due to competing priority claims and methodological challenges. The study underscores the importance of continued historical research to refine our understanding of ABA’s evolution. Rather than a single breakthrough moment, the field emerged from a gradual accumulation of experimental findings and conceptual advancements. This evolutionary process underscores ABA’s strength as a science grounded in empirical evidence and ongoing refinement.

Who Influenced Baer, Wolf, and Risley to Come to the University of Kansas?

While the foundational publications of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) are widely recognized, its institutional development was equally critical. A key figure in this process was Francis Horowitz, who was instrumental in bringing Donald Baer, Mont Wolf, and Todd Risley to the University of Kansas (KU). Horowitz, a developmental psychologist with a vision for interdisciplinary collaboration, played a pivotal role in shaping KU as a hub for behavioral research. Recognizing the promise of behavior analysis in addressing real-world problems, she facilitated the recruitment of Baer, Wolf, and Risley, setting the stage for some of the most influential research in the field. Their arrival at KU led to the establishment of a research environment where innovative applications of operant conditioning could thrive, ultimately producing landmark studies that defined ABA as a discipline.

Equally central to ABA’s institutional development was Dr. Richard Schiefelbusch, a visionary leader in speech-language pathology and child development. As the founder of KU’s Bureau of Child Research, Schiefelbusch was deeply committed to integrating research with practical applications to improve the lives of children with disabilities. He provided critical administrative and financial support that allowed Baer, Wolf, and Risley to conduct their pioneering studies on early intervention and language development. His influence helped bridge the gap between experimental behavior analysis and applied research, reinforcing the notion that behavioral science should directly impact education and therapy. Without Schiefelbusch’s leadership and commitment to research-driven intervention, ABA’s growth at KU might not have been as impactful.

Together, Horowitz and Schiefelbusch played a decisive role in founding KU’s Department of Human Development and Family Life (HDFL), which became a cornerstone for ABA research. The department fostered an environment where behavior analysts could collaborate with experts in psychology, education, and speech-language pathology, leading to groundbreaking research in child development, autism intervention, and behavior modification. HDFL became a model for how universities could integrate behavioral science into applied settings, producing a generation of researchers and practitioners who carried ABA’s principles into schools, clinics, and community programs. Their contributions ensured that ABA was not only a theoretical framework but a transformative force in improving human lives.

Did you know The Behavior Academy has an entire BACB CEU course dedicated to exploring this rich history of applied behavior analysis in Kanasa? Learn more here.

Access includes:

- 40+ self-paced video lessons by experts in Behavior Analysis, including:

- An overview of important historical developments in Applied Behavior Analysis (~4 hours)

- An overview of community-based behavior analysis and technologies outside of Autism treatment (~3 hours)

- A brief overview of the importance of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior (EAB) and how that experience transforms behavior analysts (48 minutes)

- An overview of Precision Teaching and its accomplishments (~2 hours)

- A brief overview of the current applications of behavior analysis occurring in Lawrence, Kansas (~38 minutes)

- Tours of a few select offices, including Don Baer's office. (~34 minutes)

- A total of thirteen (13) BACB® Learning CEUs are Available in the full-length course.

The Lasting Legacy of Behavioral Innovation at the University of Kansas

The University of Kansas has long been a powerhouse of behavioral research and application, with groundbreaking projects that have shaped the field far beyond its campus. One of its most influential initiatives is the Juniper Gardens Children’s Project, established in the 1960s in partnership with the local Kansas City community. This project focused on improving the educational outcomes of children in underserved neighborhoods through applied behavior analysis, particularly in literacy and early childhood intervention. Research conducted here demonstrated how systematic behavioral strategies could close achievement gaps and improve language development, making it a model for community-based intervention programs nationwide.

Another transformative contribution from KU is Achievement Place and the Family Teaching Model, pioneered by Mont Wolf and colleagues. Recognizing the limitations of traditional juvenile justice approaches, Wolf developed a behaviorally structured group home for at-risk youth, emphasizing positive reinforcement, skill-building, and self-management. This model evolved into the Teaching-Family Model, which has since been replicated across group homes, foster care, and residential treatment centers worldwide. By shifting the focus from punishment to skill acquisition and prosocial behavior, Achievement Place demonstrated how behavior analysis could offer humane and effective alternatives for youth intervention. This model is what I documented in my first film, This Way of Thinking, starring Patrick C. Friman and Sarah Trautman.

KU was also home to one of the most significant advancements in educational measurement through the work of Ogden Lindsley and his colleagues in Precision Teaching. Lindsley’s development of the Standard Celeration Chart provided a precise and systematic way to track student learning and behavior, allowing for individualized instruction tailored to students' actual performance. This innovation led to widespread improvements in special education and skills training, giving educators a powerful tool to make data-driven decisions that optimize learning outcomes. Precision Teaching remains a critical component of evidence-based instruction in ABA and beyond.

Beyond its impact in education and therapy, KU has been a leader in community-based behavioral interventions. The Community Toolbox has provided open-access resources to empower local leaders in improving public health, education, and social services through behavioral science. Additionally, Century School played a key role in Project Follow Through, the largest educational experiment in U.S. history, proving that direct instruction methods grounded in ABA produced superior academic outcomes. Further extending ABA’s applications, Deborah Altus and Keith Miller collaborated with Sunflower House to develop behavioral interventions aimed at preventing child abuse and improving child advocacy services. Collectively, these initiatives highlight KU’s unparalleled legacy in applying behavior analysis to real-world challenges, reinforcing its reputation as a global leader in behavioral science.

Decades of innovation at KU have not only shaped the field academically but have also transformed education, therapy, and community interventions worldwide. If you want to explore this rich history in greater depth, I invite you to watch The History of Applied Behavior Analysis: Part 1, available for free on The Behavior Academy. This film delves into the origins, key figures, and groundbreaking discoveries that have defined ABA, offering a comprehensive look at the science that continues to change lives.

About the Author:

Ryan O’Donnell, MS, BCBA is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) with over 15 years of experience in the field. He has dedicated his career to helping individuals improve their lives through behavior analysis and are passionate about sharing their knowledge and expertise with others. He oversees The Behavior Academy and helps top ABA professionals create video-based content in the form of films, online courses, and in-person training events. He is committed to providing accurate, up-to-date information about the field of behavior analysis and the various career paths within it.